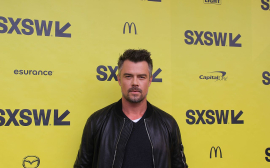

JOHNSON

Alexander

Boris

de

Pfeffel

Prime Minister of United Kingdom

Organization: Cabinet of the United Kingdom

Date of Birth: 19 June 1964

Age: 60 years old

Place of Birth: New York City, New York, U.S.

Height: 175

Weight: 78

Zodiac sign: Gemini

Activity: British politician, author, and former journalist who has served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party since 2019.

Profession: Prime Minister

Biography

Boris Johnson, in full Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson, (born June 19, 1964, New York City, New York, U.S.), American-born British journalist and Conservative Party politician who became prime minister of the United Kingdom in July 2019. Earlier he served as the second elected mayor of London (2008–16) and as secretary of state for foreign affairs (2016–18) under Prime Minister Theresa May.

Early Life And Career As A Journalist

As a child, Johnson lived in New York City, London, and Brussels before attending boarding school in England. He won a scholarship to Eton College and later studied classics at Balliol College, Oxford, where he was president of the Oxford Union. After briefly working as a management consultant, Johnson embarked on a career in journalism. He started as a reporter for The Times in 1987 but was fired for fabricating a quotation. He then began working for The Daily Telegraph, where he served as a correspondent covering the European Community (1989–94) and later as an assistant editor (1994–99). In 1994 Johnson became a political columnist for The Spectator, and in 1999 he was named the magazine’s editor, continuing in that role until 2005.

Election To Parliament

In 1997 Johnson was selected as the Conservative candidate for Clwyd South in the House of Commons, but he lost decisively to the Labour Party incumbent Martyn Jones. Soon after, Johnson began appearing on a variety of television shows, beginning in 1998 with the BBC talk program Have I Got News for You. His bumbling demeanour and occasionally irreverent remarks made him a perennial favourite on British talk shows. Johnson again stood for Parliament in 2001, this time winning the contest in the Henley-on-Thames constituency. Though he continued to appear frequently on British television programs and became one of the country’s most-recognized politicians, Johnson’s political rise was threatened on a number of occasions. He was forced to apologize to the city of Liverpool after the publication of an insensitive editorial in The Spectator, and in 2004 he was dismissed from his position as shadow arts minister after rumours surfaced of an affair between Johnson and a journalist. Despite such public rebukes, Johnson was reelected to his parliamentary seat in 2005.

Mayor Of London

Johnson entered into the London mayoral election in July 2007, challenging Labour incumbent Ken Livingstone. During the tightly contested election, he overcame perceptions that he was a gaffe-prone and insubstantial politician by focusing on issues of crime and transportation. On May 1, 2008, Johnson won a narrow victory, seen by many as a repudiation of the national Labour government led by Gordon Brown. Early the following month, Johnson fulfilled a campaign promise by stepping down as MP. In 2012 Johnson was reelected mayor, besting Livingstone again. His win was one of the few bright spots for the Conservative Party in the midterm local elections in which it lost more than 800 seats in England, Scotland, and Wales.

While pursuing his political career, Johnson continued to write. His output as an author included Lend Me Your Ears (2003), a collection of essays; Seventy-two Virgins (2004), a novel; and The Dream of Rome (2006), a historical survey of the Roman Empire. In 2014 he added The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History, which was described by one reviewer as a “breathless romp through the life and times” of Winston Churchill.

Return To Parliament, The Brexit Referendum, And Failed Pursuit Of The Conservative Leadership

Johnson returned to Parliament in 2015, winning the west London seat of Uxbridge and South Ruislip, in an election that saw the Conservative Party capture its first clear majority since the 1990s. He retained his post as mayor of London, and the victory fueled speculation that he would eventually challenge Prime Minister David Cameron for leadership of the Conservative Party.

Some critics, however, charged that Johnson’s personal political ambitions led him to be less interested and less involved in his job as mayor than he was in self-promotion. Even before leaving the office of mayor—having chosen not to run for reelection in 2016—Johnson became the leading spokesman for the “Leave” campaign in the run-up to the June 23, 2016, national referendum on whether the United Kingdom should remain a member of the European Union. In that capacity, he faced off with Cameron, who was the country’s most prominent proponent of Britain remaining in the EU, and came under criticism for equating the EU’s efforts to unify Europe with those undertaken by Napoleon I and Adolf Hitler.

When all of the votes were counted in the referendum, some 52 percent of those who went to the polls had opted for Britain to leave the EU, prompting Cameron to announce his imminent resignation as prime minister. He said that his successor should oversee the negotiations with the EU over Britain’s withdrawal and that he would step down before the Conservative Party conference in October 2016. Many observers believed that the path now had been laid for Johnson’s ascent to the party leadership and the premiership.

In the morning at the end of June when he was set to officially announce his candidacy, however, Johnson was deserted by his key ally and prospective campaign chairman, Michael Gove, the justice secretary. Gove, who had worked alongside Johnson on the “Leave” campaign, concluded that Johnson could not “provide the leadership or build the team for the task ahead” and, instead of backing Johnson’s candidacy, announced his own. The British media were quick to see betrayals of Shakespearean proportions in the political drama involving Cameron, Johnson, and Gove, whose families had been close and who had moved up the ranks of the Conservative Party together. When he left, Gove took several of Johnson’s key lieutenants with him, and Johnson, seemingly concluding that he no longer had enough support in the party to win its leadership, quickly withdrew his candidacy.

Tenure As Foreign Secretary

When Theresa May became Conservative Party leader and prime minister, she named Johnson her foreign secretary. Johnson maintained his seat in the House of Commons in the snap election called by May for June 2017, and he remained foreign secretary when May reshuffled her cabinet after the Conservatives lost their legislative majority in that election and formed a minority government. In April 2018 Johnson defended May’s decision to join the United States and France in the strategic air strikes that were undertaken against the regime of Syrian Pres. Bashar al-Assad in response to evidence that it had again used chemical weapons on its own people. Opposition parties were critical of the May government’s use of force without having first sought approval from Parliament.

Johnson himself was taken to task in some quarters for statements he had made regarding an incident in March 2018 in which a former Russian intelligence officer who had acted as a double agent for Britain was found unconscious with his daughter in Salisbury, England. Investigators believed that the pair had been exposed to a “novichok,” a complex nerve agent that had been developed by the Soviets, but Johnson was accused of misleading the public by saying that Britain’s top military laboratory had determined with certainty that the novichok used in the attack had come from Russia; the Defense Science and Technology Laboratory actually had only identified the substance as a novichok. Nonetheless, the British government was confident enough of the likelihood of Russian complicity in the attack that it expelled nearly two dozen Russian intelligence operatives who had been working in Britain under diplomatic cover. In May 2018 Johnson was the target of a prank—also thought to have been perpetrated by Russia—when a recording was made of a telephone conversation between him and a pair of individuals, one of whom fooled Johnson by pretending to be the new prime minister of Armenia.

While all these events unfolded, Johnson remained a persistent advocate of “hard” Brexit as May’s government struggled to formulate the details of its exit strategy for its negotiations with the EU. Johnson publicly (and not always tactfully) cautioned May to not relinquish British autonomy in pursuit of maintaining close economic involvement in the common market. When May summoned her cabinet to Chequers, the prime minister’s country retreat, on July 6, 2018, to try to reach a nuts-and-bolts consensus on its Brexit plan, Johnson reportedly was crudely obstinate. Nonetheless, by the gathering’s end, he seemed to have joined the other cabinet members in support of May’s softer approach to Brexit. However, after Brexit secretary David Davis resigned on July 8, saying that he could not continue as Britain’s chief negotiator with the EU because May was “giving too much away, too easily,” Johnson followed suit the next day, tendering his resignation as foreign secretary. In his letter of resignation, Johnson wrote in part:

It is more than two years since the British people voted to leave the European Union on an unambiguous and categorical promise that if they did so they would be taking back control of their democracy.

They were told that they would be able to manage their own immigration policy, repatriate the sums of UK cash currently spent by the EU, and, above all, that they would be able to pass laws independently and in the interests of the people of this country.…

That dream is dying, suffocated by needless self-doubt.

May named Jeremy Hunt, the long-serving health secretary, as Johnson’s replacement.

Ascent To Prime Minister

Meanwhile, Johnson remained a persistent critic of May’s attempts to push her version of Brexit through Parliament. After failing twice to win support for her plan in votes in the House of Commons, May, in a closed-door meeting with rank-and-file members of the Conservative Party on March 27, 2019, pledged to step down as prime minister if Parliament approved her plan. This time around, the promise of May’s imminent departure won Johnson’s support for her plan; however, once again it went down to defeat. Having failed to win sufficient support for her plan from Conservatives, unable to negotiate a compromise with the opposition, and assailed by ever more members of her own party, May announced that she would resign as party leader on June 7 but remain as caretaker prime minister until her party had chosen her successor.

This opened up a campaign to replace her that found Johnson among 10 candidates who were put to the parliamentary party in a series of Ivotes that eventually winnowed the field to four contenders: Boris Johnson, Jeremy Hunt, Michael Gove, and Sajid Javid, the home secretary. After Gove and Javid fell by the wayside in subsequent votes, Johnson and Hunt stood as the final candidates in an election in which all of the party’s nearly 160,000 members were eligible to vote. Some 87 percent of those eligible voters participated and elevated Johnson to the leadership when the results were announced on July 23. In winning 92,153 votes, Johnson captured some 66 percent of the vote, compared with about 34 percent for Hunt, who garnered 46,656 votes.

Johnson had campaigned on a promise to leave the EU without a deal (“no-deal Brexit”) if the exit agreement with the EU was not altered to his satisfaction by October 31, 2019, the revised departure deadline that had been negotiated by May. In his victory speech, he pledged to “deliver Brexit, unite the country, and defeat Jeremy Corbyn” and then rounded out the dud acronym for his pledge to dude by promising to “energize the country.” On July 24 Johnson officially became prime minister.

Faced with a threat by Corbyn to hold a vote of confidence and then confronted by a broader effort by opponents of a no-deal Brexit to move toward legislation that would prevent that option for leaving the EU, Johnson boldly announced on August 28 that he had requested the queen to prorogue Parliament, delaying its resumption from its scheduled suspension for the yearly political party conferences. The schedule called for Parliament to convene during the first two weeks of September and then to take a break until October 9. Johnson reset the return date for October 14, just over two weeks before the Brexit deadline. The queen’s approval of the request, a formality, was granted shortly after it was submitted by Johnson. Outraged critics of Johnson’s initiative argued that he was seeking to limit debate and narrow the window of opportunity for taking legislative action on an alternative to a no-deal departure. Johnson denied that this was his intention and emphasized his desire to move forward on Britain’s domestic agenda.

Opponents of a no-deal Brexit took the offensive on September 3, as members of the opposition and 21 rebellious Conservative MPs came together on a vote that allowed the House of Commons to temporarily usurp the government’s control of the legislative body’s agenda (as it had earlier done during May’s tenure as prime minister). The 328–301 vote was a humiliating defeat for Johnson, who responded vindictively by effectively expelling the 21 dissident MPs from the Conservative Party. Taking control of the agenda of the House of Commons allowed those opposed to a no-deal Brexit to set the stage for a vote on a bill that would mandate Johnson to request a delay for Brexit. Johnson sought to regain control of the narrative by announcing that he would call for a snap election. Under the Fixed Terms of Parliament Act, however, a prime minister must win the support of at least two-thirds of the House of Commons to hold such an election when it falls outside of the body’s fixed five-year terms, meaning that Johnson would have to win opposition support for that vote. The political drama heightened on September 4, as the House of Commons voted 327–299 to force Johnson to request a delay of the British withdrawal from the EU until January 31, 2020, if by October 19, 2019, he had not either submitted an agreement on Brexit for Parliament’s approval or gotten the House of Commons to approve a no-deal Brexit.

By October Johnson was able to find common ground with the EU on a renegotiated agreement that greatly resembled May’s proposal but replaced the backstop with a plan to keep Northern Ireland aligned with the EU for at least four years from the end of the transition period. On October 22 the House of Commons approved Johnson’s revised plan in principle but then quickly stymied his effort to push the agreement through to formal Parliamentary acceptance before the October 31 deadline. Thus, Johnson was compelled to ask the EU for an extension of the deadline, which was granted, and the deadline was reset for January 31, 2020. With no-deal Brexit off the table, Corbyn indicated that he would now support an early election, which was scheduled for December 12. After three failed attempts to hold a snap election, Johnson was finally able to take his case to the people, and during the campaign he promised to deliver Brexit by the new deadline. Although Johnson’s solution to the backstop pitfall looked certain to lose him the support of the Democratic Unionist Party, opinion polling prior to the election showed the Conservatives to be the likely winners and poised to gain seats. When the votes were counted, the projected Conservative victory proved to be wildly more decisive than anyone had expected. In winning 365 seats, the party increased its presence in the House of Commons by 47 seats and recorded its most commanding win in a parliamentary election since 1987. With a solid majority in place, Johnson stood poised to guide his preferred version of Brexit across the finish line.

In his address to the British people late on January 31, 2020, as the U.K. formally withdrew from the EU, Johnson said:

This is the moment when the dawn breaks and the curtain goes up on a new act in our great national drama.

Mentions in the news

Born in one day

(Dragon) .

Horoscope Gemini: horoscope for today, horoscope for tomorrow, horoscope for week, horoscope for month, horoscope for year.